Wednesday, July 25, 2012

A Wild Way To Become More Active

I'm sure that for that squirrel, when the peak tourism season comes to an end, it is a real bugger getting back up into that tree and having to go back to being a real squirrel. I have a feeling that to be a wild animal, it's a lot less stressful to just stay one than to toggle back and forth like that.

Just in case you don't know where I'm going with this, I shall now translate the above metaphor. I've found that when it comes to staying wild, it's been a lot easier for me to just learn to be wild all of the time. I think we all know several people who have tried to start exercising and quit within a few months or less. Indeed, back during my days at college I used to do a fair amount of toggling myself. Eventually, as I ran further and further, and climbed harder and harder. I began learning that to run further and climb harder, I had to eat things that made my tummy feel better and muscles feel springier. I also learned that to keep doing fun things without hurting myself, I had to keep at it even at times when I wasn't feeling it. Before long, my wild side was feeding off of itself. Eating better made me feel better which made me want to get out and play and then playing made me want to go home and eat better so I could play better the next day... whew! The cycle continued (except for the occasional breakdown like those three s'mores I "found in the forest" at last weekend... oops).

If you want to be a lightweight, strong, and just generally lean machine, then you need to eat like you're wild and move like the animal you want to be. Personally, I want to be a land endurance animal who can also scale cliffs. So I try to eat food that's reminiscent of what is in the wild, and I spend a lot of time on mountain-like terrain so my body adapts to it as if it's my natural habitat. It's a lot easier to come home from an exhausting day teaching and go for a run or get in some climbing if I am a wild animal who teaches math, rather than a domesticated teacher who sometimes goes into the woods. The more the outside feels like my home, the more I go to it.

Almost everyone wants the lean body of the wild animal that they were made to be (yes ladies, you can still be wild and shave your legs). The difficulty is that many people identify themselves as domesticated creatures who belong in houses and think that "sweet" and "fat-alicious" are the only flavors that their tongues are capable of tasting. In my experience, remembering that my body is no different in its makeup than any other wild animal in the world is a fun reminder that successful trail running and climbing really come back to letting my inner wild animal in me be free. It's been a process of several years, one that is still not complete, but I am learning that the more real food I eat and the more I spend time moving, the easier it is to keep moving.

Remember, don't immediately throw yourself into the wild and come whimpering back home. Take it easy, find stuff to love about it and remember that, just like a grizzly bear, your body was originally made to be wild. Try to enjoy an apple instead of a snickers bar. Try having one more active night a week. If the occasional chicken strip falls into your path, go ahead and eat it. Just don't be like that squirrel and permanently hang out at the Yosemite Grill eating French fries and being pitied by tourists.

PUT DOWN THAT LAPTOP AND GRAB A LOINCLOTH AND A SPEAR!

I'm getting the message from the new research loud and clear... I am a hunting and killing machine. Though I've only caught a couple of fish and shot a bird with a BB gun when I was nine (and I personally didn't eat any of them), the only thing separating me from embodying the savage cruelty of a lion is the simple fact that I don't wear a loin cloth and carry a spear.

You know Newt Gingrich, the Pope, and even that pasty white computer whiz from your dorm back in college? Merciless predators! Members of the large brained, persistence hunting top of the food chain species known scientifically as Homo Sapiens. Given a pair of moccasins, a sharpened stick, and the need to survive, Mr. Gingrich would throw aside that tie and penguin suit and take down a large bull elk with nothing more than a bit of tracking and a quick stab with a sharpened willow branch. Can you imagine the excitement and the primal power that you could feel radiating from Newt after watching him slay his prey?

If that little mental video of Newt you just watched is an image of what we humans are made for, then the question looms in my mind: What the heck? The Newt Gingrich I know would look terrible in a loincloth, may die of a heart attack after three miles of a persistence hunt, and would get a sunburn so bad that it would give skin cancer to any innocent victim so unfortunate as to look upon it. Come to think of it, most adults I can think of would be in a similar situation to Newt if they were required to go back to our persistence hunting roots.

So here's where I'm going with this. Unless some remarkable Armageddon-like situation strikes, we humans won't be going back to our persistence hunting roots. In fact, the closest thing to a persistence hunt that most of us will ever experience is walking to the meat section at our local grocery store. But I don't think that hides the fact that our bodies are designed for more. It would seem that the intelligence component of our makeup has taken over, leaving many people with stressed-out, overworked brains and atrophied, yet strikingly plump, bodies.

Most people think I'm kind of a nut. I run or bike or climb for several hours most days (although it is less during the school year when I'm teaching). I'm sure that some would argue that I'm obsessed or addicted. Yet for me, my life has never made more sense. I really dislike the stresses of our modern world. We are required to keep track of several bank and loan accounts, pay five or ten different bills every month, mow our lawns, fix our houses, maintain cars and computers and toilets, raise children, maintain contact with friends from all over the world, and on top of all that we have to keep up with a job and its multitude of tasks. I wonder why it is that the National Institute of Mental Health reports that more than 1 in 4 Americans suffer from a diagnosable mental illness?

Personally, I think our mental illness issue is a consequence of our minds being overworked, while our bodies remain under-worked. The more "intense" I become in my outdoor sports, the more I realized that they inspire me toward simplicity. When I begin to enjoy three hour runs, having a pimped-out ride becomes less of a priority and just having water and good food becomes my focus. When I spend more time outside working toward my next ultramarathon, owning a nice, expensive house begins sliding down my list of priorities. When I long to be moving in the mountains at the end of the work day, suddenly negotiating for a 1% raise at work becomes of little importance. With less to worry about, and more time moving and exploring, I am just flat out, way happier.

Even though our intelligence as humans has created a society that has almost no demand for using our physical prowess, I believe that movement is still an essential aspect of what it is to be human. In order to counteract the constant mental demands that we face from our world, we have to find ways to move and use our God-given ability as endurance athletes. By finding a love for something involving movement (even if it kind of hurts), I think it is possible to begin to eventually diminish the importance of some of the stress makers in our lives. Perhaps there will even come a time when more of us will once again look sensational in a loin cloth and spear as we chase a large herbivore across the prairie.

Monday, July 16, 2012

Mentally Coping With Long Runs

Fast forward six months, and I was signing up for an 50 mile run, and the terrible thoughts from that 15 miler during the previous summer were haunting me. Certainly, I would fail. Little did I know, but a great power was building within me. A force that would shield my fragile mind from the horrors that sometimes must be confronted on a long run. Now I come to you, dear reader, for I desire to share my new knowledge of this force.

So here's how it works!

Guy A goes for a run. Guy A starts thinking about how great it will feel to be done with that run. Guy A starts fantasizing about a couch and that tasty pizza that Guy A will have when he completes that run. It is then that the full gravity of the situation falls upon Guy A. Guy A wants pizza and a couch... now, and the rest of the run is dumb and in the way of said pizza! Running is now Guy A's punisher, his obligation, and his enemy. Guy A shortens his run to be done with it. Guy A weeps. Guy A's pizza tastes of ash.

Let's now contrast that with Gal B. Gal B goes for a run. Gal B leaves thinking about her favorite parts of the route that Gal B will travel. Gal B brings money and a small snack. Gal B thinks about how cool it will be to have run the distance before her, but relaxes and lets her mind wander and is in no hurry to finish. If Gal B starts feeling too much pain, Gal B slows a bit for a while because she has the ability to ignore her ego. If Gal B ends up longing for food, she has a snack or has a chocolate milk at a gas station. Gal B ends up running three extra miles and enjoys her post-run pizza, made tastier by the pride of knowing what she was just able to accomplish.

So here's the summary for bullet-list people:

- Find the least painful route possible if there are none you totally like, and think about your favorite parts of it.

- Bring money and/or a snack so you can stop cravings that come up.

- Relax and don't dwell on being done. Try to enjoy being out there.

- Let your mind wander and don't be afraid to think about how cool what you are accomplishing is.

- Let go of your ego. It's better to be running slow that not running at all. Speed can come later when your more callused to the distance.

Keep in mind that you will get better at these the more you run. It takes time to be able to relax and not think about being done and eating pizza. Some days are just mentally better than others, and that's okay. The key is getting better over time and learning to love running and not just see it as a punishment or self-inflicted boot camp. I've ran for over four hours on many occasions, and I still have the occasional breakdown on runs that are less than ten miles... but I'm getting better all the time.

Friday, June 29, 2012

The Path To My First Ultramarathon (ATTN: Less Training Needed Than You May Think)

Here's the data on what got me to and through my 50-mile mountain run. For much of the training I did, I skipped much of the mid-week runs that I was "supposed" to do so that I could go rock climbing. I only focused on completing the long weekend runs, and I never did a full 30+ miler as the plan suggested.

The Base:

- Active childhood riding bikes and running around

- Played Football and was a Montana all-state hurdler in high school (never competed in anything over 800 meters)

- Began hiking frequently and then summiting 12,000 ft mountains when I was about 16

- Never really ran more than about 5-6 miles at a time until a couple of years ago.

- Never regularly (more than once every couple months) ran 10 or more miles until last fall

- Had ridden my bike 60 or more miles on less than 10 occasions

- Had never run a marathon.

The Training:

- Decided to sign-up for the 50 miler in early January

- Began by running several times a week with a long (10-15 mile weekend run) for just over a month.

- Began running 20 miles for my long weekend run after about a month. They hurt quite a lot in the last 5 miles.

- Began losing interest in running and nearly ceased running mid-week (partly because I was rock climbing a lot) during the months of April and May. Continued to run 20-25 miles every other weekend during that time.

- The long runs in May were trail runs (which I quite enjoyed even though they still hurt).

- In early June, I tapered back from 16 mile long runs to an 8 miler the weekends before the event.

- First 18 miles of trail downhill went well

- Began to get tired in nauseous on powerhike/run section for next 17 miles

- Most of body was stiff and achey and slight nausea continued for next 5 miles.

- Had to walk last major downhill due to leg muscles and knee being sore.

- Mostly walked last 5 miles (no longer on trail... on road) as dehydration, faintness, and exhaustion overtook me... but I did finish.

The Recovery:

- 2 days of sore leg muscles and somewhat sore knee and ankle joints that caused me to walk like an old man.

- muscles seemed mostly recovered and full strength within about 5 days.

- was back doing difficult mountain bike rides a week later.

- Avoided running due to a slightly sore knee and heel until 2 weeks after event

- Began easy runs with some ankle and knee stiffness which is not getting worse.

The Conclusion:

- I didn't finish as fast as I would have liked, so for future 50 milers I plan on increasing the volume of trail runs and to run more mid-week so that I can maintain a higher intensity for longer.

- I need to practice keeping hydrated and feeding myself during these long events... something training plans don't work into the schedule.

- I don't regret failing to run as much as I "should" have according to the plan. I feel that my lighter training approach allowed me to not get burned out. Having completed the event, I now feel that I have matured and that I mentally can handle more training than before as I attempt to run a faster time.

- I believe that this more layed-back approach to training can work whether you're a former athlete attempting an ultramarathon or a non-athlete or out-of-shape person attempting a 5k.

- For me, the key to becoming a stronger runner is to train my mind to be able to train!

Thursday, June 21, 2012

My First Bighorn Mountain Run (50 Mile)

|

| Crossing the Little Bighorn River (mile 18) |

Sunday, April 29, 2012

It's Gettin' All "Spiritual" Now

Almost every time I step outside these days and feel the breeze, see the stars, grass, or mountains, I feel a presence of God. It often drives me to want to move. Through movement and physically challenging myself outside, I feel like I am a part of something much bigger than myself. I feel this amazing sentimental attachment to the rocks I climb, and I marvel at the boulders, cliffs, and handholds as if they are a sculpture by an unrivaled artist. When I move my body to climb the rock, it almost feels as if the rock is teaching me the moves to a dance... every climb having its own unique choreography; some light and beautiful, others aggressive, powerful, and sometimes frightening. I love how it smells so good and how nature is often so pristine, but also dirty, dangerous, and asymmetrical. I do get really angry out there at times, I even have yelled out sonnets of unfriendly words at God when I've gotten stuck in a blast-furnace headwind or freezing rain. But at the end of the day, the passion and imperfection of the whole experience just makes me crazy for more.

I realize that this movement and dance with the natural world I get to experience connects me to something fundamental about how God made me... with ability to move and sense nature. The passion I feel challenging myself in the natural world is unrivaled by anything I ever experienced in church, and I often wonder how many people are like me. For years, they try to make themselves feel a connection to God in church but always feel a bit off-kilter. They wonder how it is that others* love the singing, sermons, and Bible verses. In their own thoughts, they daily question whether God is real because they secretly feel as though they have never actually encountered Him in a way that they can understand. They await miracles... will them to happen to confirm God's existence, but always come up short. To them, church feels like a game of pretend, but they stick with it. They talk the talk to be accepted because there is nowhere else to go. Eventually, some do leave, and sometimes they leave God behind when they go.

I remember when I was a regular church goer**, I used to experience a great deal of fear and guilt over my inability to "share my faith" with "non-Christians". I was awkward when I tried, but now I can unashamedly say that there is something in the fabric of nature that awakens something in the fabric of me. I can't fully describe it, but I love it. Without giving it a second thought, without the need for philosophy and theology, I call it God and start talking to it. It makes me want to let go of resentment and guilt and just live. It makes me want to share it with other people. It gives me confidence that helps me be a better person.

So I guess my question is... what awakens something in you? Acting, science, building??? May I propose that it is God interacting with you in a way that is truly special for you? Do you feel your problems and resentments shrink away as you do it? Whether you think I'm nuts or not, I suppose it's worth considering. I sure think it's neat.

Sunday, February 19, 2012

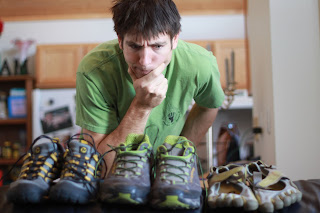

Barefoot vs. Moonboots

Alright, so there is a raging argument between which is better: barefoot running or running in super-technical running shoes with microchips and stuff. (Seriously, Adidas came out with one a few years ago that would adjust cushioning for different runners.)

A couple of years ago, I was running in a pair of Five Fingers, and I was told by a non-runner who had read a few articles on the matter, that barefoot running would destroy my arches. When the book Born to Run came out, running barefoot became such a big deal that you'd have thought it would cure cancer. It seems like there are a lot of people that feel very strongly on this matter either one way or the other. It's not hard to find comments online where people are dropping F-bombs back and forth at each other over their certainty that one form of footwear is superior to the other.

Let me shoot for the middle here. I have tried barefoot running and I have also spent considerable time running in techy, very cushioned shoes. Here is what I have found.

Barefoot running makes you feel like either an indigenous man in a loin cloth or a varmint running the streets and trails. Either way, it is smooth, quiet, and a lot of fun, but...

Barefoot running can be painful, especially at first. Your lower calves will scream at you and the bottom of your feet will get worked-over pretty well. You'll also run a bit slower and need to shorten and quicken your stride, as hitting your heel with those big, long strides from high school track will really smart. But within a month (even a couple of weeks), it isn't too bad at all, especially over shorter distances (<7 miles for me).

If you dive into barefoot running too quickly, you will likely get injured... duh. This idea seems to allude many people, especially those who swear by their cushy shoes. I would expect that a break-in of several years would be necessary to become injury resistant at distances that one used to do in their cushy, supportive shoes.

I have a feeling that some people may just have an anatomy that will never allow them to barefoot run for very long. It stinks, but it is true. Being raised with your feet living basically in the casts (fancy, supportive shoes) may make switching very difficult.

Barefoot running teaches you to run in such a way that your knees, hips, lower back, and shins will thank you. This means your feet don't strike out in front of you and you strike mid foot. You will have to shorten and quicken your stride to do this, but it is actually way more efficient anyway. Here is the truly novel thing... you don't actually need to have barefoot running shoes on to run this way. Especially if you can find a shoe that doesn't have too big of a heel rise in it.

So, which is better? BOTH!!! They are each good for different reasons, and both have their issues. Personally, I use bigger shoes when I am pushing my distances, running in the winter, and running rocky trails. I use my more minimalist shoes when I'm running for fun on warmer days and sometimes just for the heck of it other times as well. I would like to be running exclusively in minimalist shoes in the next five or ten years, though, as I just really like the idea of it.

Periodization

Beginning the HIT strips as well as several injuries have taught me the importance of varying the intensity of training. Basically, all serious athletes do it if they have a clue about how their body works. When I do the weighted HIT strips more than 5 times in a row (~2 weeks when the mandatory 48-72 hour recovery is included), my fingers begin to feel a little tweaked and my weights begin to decrease slightly. This is known to some as cumulative fatigue.

It's then time to take an extra day off and then climb without weight for a while in sets that are long enough that they make you want to whimper over how bad your muscles are burning (called power endurance training). I usually do this for about 2 weeks as well.

After the power endurance, it's time to take a few weeks to climb some endurance (the fun climbing on easy routes that allows one to work on coordination and never be in much pain).

After the endurance weeks, it's time to take a week off and then hit the really intense strength training again, starting the cycle over.

This periodization principle, is one of the keys to increasing injury resistance and to avoid plateaus. Plus, the varying intensity can be synchronized with another sport (running in my case), and during the less intense phase in one sport, you can schedule the high intensity time in the other. This is one of the things that is allowing me to train for an ultramarathon while still not seeing a crash in my climbing strength. It also keeps me from growing to passionately hate one of the sports.

HIT Training is Working Stupendously!!

I find it a little frustrating how very few people seem to post on what they do in their training that is working, so since I've tried a few things that have really worked recently, I thought I should share. A lot of the stuff I have learned will translate well for people in other sports besides climbing and running.

HIT Strips

As shown in the picture, these are basically just big climbing holds that have pocket, crimp, and pinch options. The workout I'm doing (as per the instructions that from Eric Horst, the inventor) involves doing two sets of up to twenty hand moves with each grip with exactly a three minute rest. To keep reps under twenty, you add weight to yourself.

Results:

I really started counting the weight increase after I had done it for two weeks, as the first couple of weeks involve a rapid increase due to training muscle coordination so that you can pull harder with the same muscles. This continues to happen after two weeks, but to a much more consistent and less wildly rapid degree.

When I officially began recording weights I could not complete twenty reps with the following weights for each grip:

Pinch: 5 lbs

Open crimp: 25 lbs

Closed crimp: 0 lbs

Index/middle finger team: 5 lbs

Middle/ring finger team: 0 lbs

Ring/pinky finger team: Not doing due to injury

Just this last week (4 months of training), my weights had risen to:

Pinch: 35 lbs

Open crimp: 55 lbs

Closed crimp: 35 lbs

Index/middle finger team: 55 lbs

Middle/ring finger team: 50 lbs

Ring/pinky finger team: Still not really doing due to injury in forearm.

I can say that a bit of the increase in weights can be attributed to whole body muscle memory making the HIT strip climbing process more coordinated, but a recent change to some really crappy shoes that coincided with weight increases even with my feet occasionally popping off show that the strength increase I have seen is very legitimate.

One other note that I should make is the even though the HIT strips are designed to target finger strength, I have noticed that my pullup test has gone up more rapidly since beginning HIT training. I had been working my pull muscles consistently since the beginning of 2011, and I have gone from ~16 to ~25 ( taken post workout, so some fatigue existed) at a time. My pullup ability seemed to plateau during the spring in the upper teens, but then jumped to ~25 in the late fall.